Sarah (3rd great aunt), the eldest child of Charles and Margaret Lutton arrived from Ireland with her parents in 1844. She was born in County Down on 27 May 1840 and arrived in Sydney aged three in January 1844.

When her parents relocated to Queensland (about 1852), and then back again to Sydney in about 1854, she remained in Queensland. In 1854 Maurice O’Connell (the younger) became Governor resident in Port Curtis, Rockhampton. Sarah, aged 14 stayed in Queensland as part of the 'household' of O'Connell, probably as a servant.

When her parents relocated to Queensland (about 1852), and then back again to Sydney in about 1854, she remained in Queensland. In 1854 Maurice O’Connell (the younger) became Governor resident in Port Curtis, Rockhampton. Sarah, aged 14 stayed in Queensland as part of the 'household' of O'Connell, probably as a servant.

About 1867 Sarah married a man named Charles Baldwin who was the parliamentary caterer. He was an Englishman of some means. They had children:

- Charles James, born 11 February 1868 in Brisbane. Married about 1896 to Margaret McGreachin, and had five children;

- Maurice Ernest William, born 17 July 1869 in Brisbane, married 25 February 1892 to Maggie Louisa Mildred Angus;

- Arthur Gilbert, born 11 October 1870 in Brisbane, married 31 May 1893 to Esther Brennan. They had three children;

- Louisa Margaret Maude, born 6 May 1872 in Brisbane, married 25 February 1898 to Frederick Charles Woosley and had one son, then married someone else and had 3 children;

- Henry Albert St John, born 21 December 1873 in Brisbane;

- Beatrice Caroline, born 19 November 1875 in Brisbane, married John Samuel Wiley on 8 May 1895, and had 4 children;

- Edgar Friday, born 30 April 1877 in Brisbane.

Betty Lahiff's narrative says that Sarah died in childbirth in 1878. However, a contemporary newspaper notices (The Telegraph, Brisbane Wed 9 Jan 1878 p2 and The Brisbane Courier Thursday 10 Jan 1878 p 2) says that she died on 9 January 1878 at the Parliamentary Refreshment Rooms (presumably Charles' workplace; possibly it included accommodation) after a 'short and painful illness'. Elsewhere I have seen it described as peritonitis.

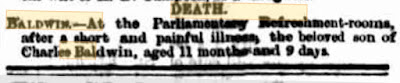

Sadly for Charles, a month later The Brisbane Courier carried a notice of the death of a son. "At the Parliamentary Refreshment-rooms, after a short and painful illness, the beloved son of Charles Baldwin, aged 11 months and 9 days." That would be Edgar Friday who was born 30 April 1877.

Mary, Charles' and Margaret's second daughter, travelled to Brisbane to housekeep for the family. Charles Baldwin eventually proposed marriage to Mary, which was accepted. They had 2 daughters, Violet and Ruby.

Fanny Lutton (3rd great aunt) (by Betty Lahiff)

|

| The Telegraph Brisbane Wed 9 January 1878 p2 |

Sadly for Charles, a month later The Brisbane Courier carried a notice of the death of a son. "At the Parliamentary Refreshment-rooms, after a short and painful illness, the beloved son of Charles Baldwin, aged 11 months and 9 days." That would be Edgar Friday who was born 30 April 1877.

Mary, Charles' and Margaret's second daughter, travelled to Brisbane to housekeep for the family. Charles Baldwin eventually proposed marriage to Mary, which was accepted. They had 2 daughters, Violet and Ruby.

Fanny Lutton (3rd great aunt) (by Betty Lahiff)

"Fanny, the youngest surviving child of Charles and Margaret Lutton was born in 1861 in Sydney, and was a remarkable woman.

"Her photos show her as a good looking young girl. A proposal of marriage from a son of the wealthy Farmer family (the big Sydney retail company) was refused. Fanny considered it was her duty to care for her aged parents. Aged pensions and social welfare payments had not been introduced in those times.

"She worked as a tailoress at home, as well as performing housekeeping work. An ardent parishoner at St Peter’s Church of England, Woolloomooloo, she trained as a Deaconess, and spoke on Sunday afternoons from a religious platform in the Sydney Domain. Fanny, as part of her church work, also trained in midwifery nursing and worked in “the Loo” district. Parts of “the Loo” were very rough, with very many poor people. She wore her Deaconess uniform, something like a nurse’s dress, when attending people, and was never molested, even in the toughest places. The people respected and trusted her.

|

| St Peter's Anglican Church Woolloomooloo - a working class church |

"When her parents died in 1898, Fanny realised she was alone, without a family, and with no future in Sydney. She made application to her Church of England to join the misisonary service but was rejected as being over the age limit of 35. She was less than 37 years of age.

"A Dr. and Mrs. Zeimer, American medical missionaries, were in Sydney at the time and after some discussion with Fanny, it was agreeed that she would go with them, I think to India, as part of their medical team. This was a happy arrangement.

"Fanny became an American citizen and enjoyed an interesting and useful life. From India she was posted to Arabia, or Mesopotamia, as it was called then. A requirement of her training was to read and write Arabic, no mean achievement for a woman in her forties. When she returned on her frst long-service leave, about 1910, she continued her study of the language, greatly amusing her nieces and nephews when reading her Arabic Bible aloud.

"During one long leave, she planned to journey to Northern Ireland to meet her parent’s relatives. It is not certain that she did visit Ireland.

"About 1921 she returned again to Australia for long leave. Although I was only a small child, I remember being impressed by her personality - she was “different” form our other aunts. During this visit she arranged for my mother to hand-knit her a pair of black silk stockings on the finest needles. My mother completed the stockings, but refused to ever again knit silk stockings. Aunt Fanny probably thought she was helping my mother financially.

"One Sunday she had midday dinner with the family in Merrylands. Granny dutifully said grace when Grace Lahiff, about 5 years old, announced “we don’t always do this”.

"The work of a missionary was restricting, although she travelled in many countries in the Middle East, and her outlook on life became narrow in some ways. She did retain a sense of humour though. At her niece’s home in Brisbane, she commented that a nude statue was not suitable in a home with young children, to be given the reply - “Aunt, to the pure, all things are pure”. People overseas assumed she was part of Sydney society and inquired if she knew the Governor. She just smiled to herself and said afterwards - “I remember him, we were barefooted children running down the street to wave as his carriage went by”. These, and similar incidents, gave her many a laugh.

"Looking back, criticism by her relatives that she was narrow-minded was most unfair, in view of her devotion to her family and her work among the poor people of East Sydney.

"When retirement came, she elected to live in the U.S.A. instead of returning to Australia. While there she met another distant cousin, Dr. George Lutton of New York. She was happy among her friends there. Correspondence was maintained with relatives in Australia. During the war she wrote of standing in queues for food.

"Fanny died in 1947, aged 86 years. The family did have newspaper clippings of Fanny Lutton speaking in the Sydney Domain and also of her farewell function from S Peter’s Church, Woolloomooloo.

[NOTE: Sydney Anglican - A History of the Diocese, S. Judd and K. Cabbe, 1987, records that Fanny Lutton was admitted as a deaconess to the Sydney Diocese.]"

Fanny's work is mentioned in a book called The Arabian Mission's Story: In Search of Abraham's Other Son by Lewis R Scudder. The missionary work was set up by the Dutch Reformed Church of America.

"Fanny Lutton was assigned to Oman to work with women in 1911. The site chosen for the new medical work was the marginally more healthy town of Matrah, separated from Muscat by a ridge of black basalt rock. Access into the interior of the country was easier from Matrah.

"Fred Barny continued to manage the Muscat endeavours of school and Bible shop. Fanny Lutton was assigned to women's evangelistic work in Muscat. Although hampered by the rebellion of the interior against the sultans of Muscat, an important part of the work in Oman was evangelistic touring."Jerzy Zdanowski's book Saving Sinners, Even Moslems: The Arabian Mission (1889-1973) and its Intellectual Roots mentions Fanny:

"The third single woman to join the Arabian Mission was Fannie (sic) Lutton. She became a missionary in 1904 and came to Bahrein from Australia. She learned Arabic very well and worked until retirement as an evangelist for Arab women and children. During her years of service she was stationed in turn in Basrah, Bahrein, Muscat and finally in Amarah."

Following is a piece written by Fanny Lutton titled Everyday Life in Bahrein, in the Arabian Mission Newsletter of April-June 1905:

Fanny died in Brooklyn, New York on 8 December 1946.

"There are many people who would say to us: "I suppose you have little or no romance in your life every day in Bahrein?" In a sense this is true; but still, life here is not monotonous by any means. I think a woman worker has far more variety in missionary work; because she is a woman. She has the privilege of entering the homes of the people and can always get an audience of women. She can always carry books with her, and very often the opportunity is given her to read.

"I wish you could have come with me to two houses, and you would have said, "What a contrast in the two places." The first house I entered, I saluted the woman who was near the entrance, but her manner was not very cordial. I then asked for the lady of the house, and the answer was given: "Oh, she died last year from cholera." Just then a little boy came to me and asked me to enter a room (a kind of out-house) where there was a poor old woman very sick. The poor old woman entreats me to prescribe for her. I tell her I am not a doctor, but will bring one to see her. Mrs Thoms comes at my request. By that time the news had gone abroad, and many of the neighbours assemble in the courtyard. The old woman is in such a filthy condition, and this stable (for that is really what it is) so dirty.

Mrs Thoms asked some women to wash the sick one; but no one will do it. There is nothing else for it, so Mrs Thoms and I set to and give the poor old woman a good bath and put clean clothes on her. Now the next step is to get the place cleaned, and about four or five women begin to clean up. Could you have seen the collection of old rubbish you would not have forgotten it. One woman said, "This has not been cleaned for twenty years," and I will believe it. We stayed until the place was cleaned, and the sick one placed on a clean mat; and really, the old woman and room looked like a transformation scene.

Mrs Thoms and I had to laugh when we saw the clouds of dust ascending. But we had the satisfaction of seeing the sick one more comfortable, and of getting her thanks also.

The next house visited is very different. The people are very cordial, and ask the reason of my long absence. As I count the women I see nine around me, and then one notices the hand-bag I have with me, and wants to know "What is in it?" I tell her. "It is the Word of God good news." One says "Is it the Koran?" I answer, "No. But it is written in your Koran that the Gospel was sent down from God for the guidance of men, and we should not neglect the reading of it." All exclaim, "Oh read to us" and now comes the opportunity of proclaiming the good tidings.

I can tell you I left that house with a thankful heart, just because I had had the privilege and opportunity o witness about the Sinless Prophet, Who gave Himself a ransom, and Who invites the "weary and heavy laden" to come to Him for rest.

Oh, do pray for the poor women in Arabia, who have so little to cheer them, and who are living in darkness and error. "

The Arabian Mission Annual General Meeting 1929

|

| Arabian Mission Annual General Meeting 1929. Fanny is in the second row, third from left. |

No comments:

Post a Comment